Share

Antique Bibles for Sale: A Short History of the English Bible (with a 17th‑Century Example)

Antique Bibles for Sale: What a 17th-Century Holy Bible Can Tell Us

We were delighted to be able to offer a rare 17th-century antique Bible for sale recently - a London-printed volume dated 1638-1639, with four title pages and an inscription from 1652. It’s the kind of book people have in mind when they talk about antique bibles for sale, and it raises a simple question: what exactly are you looking at when you hold a Bible this old?

It isn’t a single work written in one go, but a collection of texts produced over many centuries, covering everything from law and history to poetry, prophecy and letters. For most of history, ordinary people didn’t own a Bible at all, let alone one in their own language. That only really changed once printing arrived and English translations became more widely accepted.

The result, over time, is the sort of 17th-century Bible that still occasionally turns up in specialist bookshops today. At J.W.B Books we’ve handled a number of older bibles & religious titles, and this particular Barker-printed Bible is a good example to use when talking about what makes an antique Bible interesting.

For most of history, people didn’t encounter the Bible as a personal printed book on a shelf. They heard it read aloud, saw it in handwritten manuscripts, or knew it through fragments and quotations. The idea that an ordinary person might own a complete Bible in their own language is relatively recent. That’s what makes antique bibles so fascinating. They’re not just religious texts; they’re physical witnesses to how people in different centuries read, heard and handled scripture.

From Manuscript to Print

For over a thousand years in Western Europe, the Bible of the church was the Latin Vulgate, associated with St Jerome. Copies were handwritten by scribes on parchment or vellum. Producing a full Bible could take months or years, and the result was expensive and rare. A large church or monastery might own one; most people would never see a complete Bible.

The invention of printing in the mid-15th century changed the technology but not immediately the language. Gutenberg’s famous Bible of the 1450s was still in Latin. It was a huge step forward in production, but not yet a Bible for ordinary English readers.

The Desire for an English Bible

By the late Middle Ages, there was growing pressure for scripture in the language people actually spoke. In the late 1300s, John Wycliffe and his circle produced English translations of the Bible from the Latin Vulgate. These were still handwritten manuscripts, not printed books, and they were controversial enough that Wycliffe’s work was later condemned. English Bible translation without church approval was banned.

By the early 1500s, three big changes came together:

1) Printing technology made books cheaper and more widely available.

2) Humanist scholars were going back to earlier Greek and Hebrew sources.

3) At the same time, reformers were arguing that ordinary people should be able to read the Bible in their own tongue. Together, those forces set the stage for the first printed English Bibles.

The First English Bibles in Print

William Tyndale is the key figure in the early printed story. A gifted linguist, he believed that even "the boy that driveth the plough" should be able to read scripture. Using Erasmus’s printed Greek New Testament and his own knowledge of Hebrew, he translated the New Testament into clear, direct English.

In 1526 his English New Testament was printed and smuggled into England. Authorities tried to seize and burn copies, but enough survived to circulate widely. Tyndale continued working on the Old Testament, but he was eventually betrayed, tried for heresy and executed in 1536.

Despite his fate, Tyndale’s work lived on. Later translators borrowed heavily from his phrasing. Many familiar lines in the King James Bible - "Let there be light", "the powers that be", "the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak" - echo Tyndale’s wording. When you hold a 17th-century English Bible, you’re still hearing Tyndale’s voice in the background.

After Tyndale, others picked up where he left off. Miles Coverdale produced the first complete printed English Bible in 1535, drawing on Tyndale and other sources. The Matthew Bible followed in 1537, combining Tyndale’s translations with additional material. In 1539, the Great Bible appeared - a large English Bible authorised for use in churches. King Henry VIII ordered copies to be placed in parish churches across England.

Within a few decades, an English Bible had gone from something that could get you executed to something the king wanted in every church.

Geneva, Bishops and Douay-Rheims

By the second half of the 16th century, English Bible publishing had become crowded and political. The Geneva Bible, produced by English exiles in Geneva, was designed for ordinary readers. It was smaller, printed in a clear Roman typeface and packed with marginal notes explaining the text. It quickly became the people’s favourite and was widely read in homes as well as churches.

The Bishops’ Bible, commissioned by Archbishop Matthew Parker, was the Church of England’s response. It aimed to update the Great Bible and provide a more "official" alternative to Geneva. Often printed in large folio format with handsome woodcut illustrations, it was beautiful but never quite matched Geneva’s popularity.

On the Catholic side, English scholars working in Europe produced the Douay-Rheims Bible. It was an English version of the Latin Bible, with notes written from a Catholic point of view.

By 1600, English readers had several different Bibles, each with its own theological flavour and set of notes. Many church leaders wanted a translation that could be read in every parish without stirring up controversy.

The King James Bible and the 17th Century

In 1604, King James I authorised a new translation of the Bible into English. Teams of scholars worked from Hebrew and Greek texts, revising earlier English versions and aiming for something both accurate and dignified. They were told not to add lots of opinionated notes, and to produce a text that would work well when read aloud in church.

The first edition of the King James Bible appeared in 1611. It didn’t instantly replace all other versions, but over the course of the 17th century it gradually became the dominant English Bible.

From a book-history point of view, this period is especially rich:

- Printers experimented with different formats: large folios for pulpits, and smaller, hand-sized Bibles for personal use.

- Bibles were often issued with additional material: genealogies, maps, concordances, psalms and prayers.

- Different printers and cities produced their own editions, sometimes with small textual variations and distinctive title pages.

By the 1630s and 1640s, English Bibles were recognisably "modern" in their language but still early in terms of printing history. This is the world to which many 17th-century antique bibles belong.

A 17th-Century English Bible from London

One 17th-century Bible we recently handled at J.W.B Books illustrates many of the features people look for in early English Bibles. The Bible was printed in London in the late 1630s. It wasn’t a huge pulpit folio, but a hand-sized book around 17.1 cm tall - the sort of Bible that might have been used in a household or carried to church.

Four Title Pages in One Book

Instead of a single title page like we tend to see nowadays, the book contained four:

-

"The Genealogies Recorded In The Sacred Scriptures, According To Every Family and Tribe" - dated 1638

A series of printed genealogies, laying out biblical family lines in chart form. -

"The Holy Bible Containing The Old Testament and The New" - dated 1639

The main title page for the complete Bible text. -

"The New Testament of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ" - dated 1639

A separate title page for the New Testament, as was common at the time. -

"A Brief Concordance or Table To The Bible of the Last Translation"

A concordance - essentially an index of names and themes - to help readers find passages.

Together, these sections show how a 17th-century Bible could function as a mini-reference library: scripture, genealogies and a search tool bound into one volume.

Printer: Robert Barker

The title pages name Robert Barker as the printer. He was royal printer to King James I and responsible for some of the early King James Bible editions, and his workshop was closely involved in spreading the new translation in the first part of the 1600s.

A Bible with a 1652 Inscription

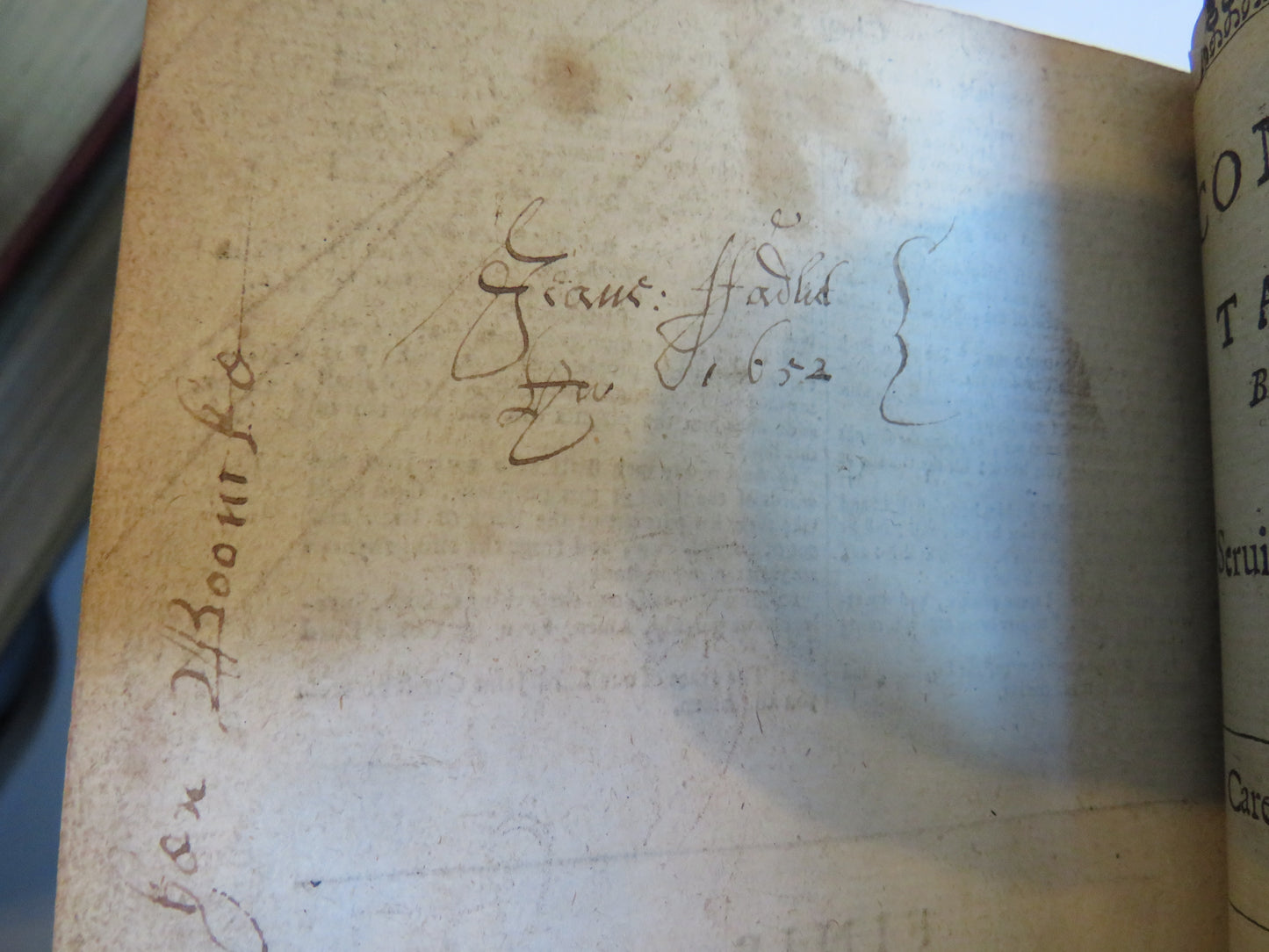

One detail that stands out in this Bible is an inscription dated 1652, written in an early hand opposite the final title page. It’s a small note, but it places the book clearly in its own century and hints at the life it had with its early owners. For many readers, details like a mid-17th-century inscription are what turn an antique Bible from an abstract historical object into something much more personal.

What to Notice When You Look at an Antique Bible

When people browse antique bibles for sale, they’re often drawn straight to the date. That matters, but there are a few other simple things worth noticing. First, look at the title page. The printer’s name and the place of publication help you place the Bible in time. In this example, seeing Robert Barker’s name tells you you’re in the early King James period.

Next, look at how the book is put together. Extra title pages, printed genealogies and a concordance show that this Bible was meant to be used as a kind of all-in-one reference book, not just something to sit on a lectern. Then look for signs of ownership. A dated inscription like the one from 1652 in this copy gives the book a human story as well as a printing history.

Finally, and especially if you’re thinking about value, take time to look at the condition of the book. Age plays a big part in how a Bible has survived, but condition can also make a huge difference to price. You don’t need to think like a specialist collector, though. If you can notice the printer, the structure, the personal traces and the overall condition, you’re already seeing more than just “an old Bible”.

Caring for Antique and Old Bibles

Whether your Bible is a 17th-century rarity or a later family volume, a few simple habits will help it survive.

Storage

- Keep Bibles in a stable environment - avoid damp, direct heat and strong sunlight.

- Large, heavy Bibles are often happiest stored flat; smaller volumes can stand upright, supported by neighbouring books or bookends.

- Avoid attics, garages and cellars, which are prone to extremes of temperature and humidity.

Handling

- Wash and dry your hands before handling old bibles; clean, dry skin is usually better than gloves.

- Support the spine when opening the book and don’t force it to lie completely flat if it resists.

- Turn pages gently from the middle of the edge rather than pinching the corners.

Repairs and Conservation

- Avoid modern sticky tape and household glues - they cause long-term damage.

- If pages are loose, it’s often better to keep the book in a protective box or wrap rather than attempting DIY repairs.

- For particularly valuable antique bibles, professional conservation advice is worth seeking, especially if the spine is detached or there are signs of mould. For more information on caring for rare books, see our guide.

Why Antique Bibles Are Worth Exploring

From handwritten Latin manuscripts to small printed King James Bibles, the history of the printed Bible is bound up with the history of reading itself. Each antique bible carries that story in its pages: the choices of translators, the skill of printers, the habits of readers who turned those pages long before us.

A London Bible from the 1630s, with its genealogies, concordance and 1652 inscription, is just one example of the kind of volume that still surfaces today. It’s fragile, yes - but it’s also a tangible link to the world that produced the King James Bible and lived with it day to day.

If you’re curious about this world, browsing current and past examples of antique bibles for sale is one of the best ways to learn. Over time you start to recognise printers, layouts, features and eras - and you’ll know when a particular Bible really speaks to you.

At J.W.B Books we regularly handle older bibles & religious titles, including 17th-century examples like the one described here. Our stock changes constantly, but we’re always happy to share the stories behind the books that pass through our hands. Take a look at our current collection of Bibles and Religious books.